In the early morning hours of Thursday, May 21, 2020, Lana Del Rey awoke the internet with the not-so-startling news that she suffers from late-stage white woman victimhood. The symptoms include dehumanizing Black women, refusing to acknowledge one’s white privilege, denying all accountability, desiring to speak one’s opinion without suffering from the inevitable consequences, and ignoring the lack of intersectionality that permeates mainstream feminism.

Given the overwhelming amount of backlash she has received for confirming her prognosis (even after two weeks have passed), I would hate to provide her with more free press. However, as someone who identifies as a former fan of hers—heavy emphasis on that former, beloved—I feel the urge to provide a retrospective that encompasses how her victimhood has progressed to this point. It appears that she has now reached the stage where she shows the uncontrollable proclivity towards microaggressive behavior.

Aside from Ariana Grande (a white woman with her own claims of cultural appropriation to address) and Camila Cabello (a white Latina with her own controversies attached to anti-Black sentiments), Lana’s list of “peers” targets women who exist as partially Black or fully Black. Doja Cat is a biracial woman, being half-Black and half-white. Social media frequently debates the race and ethnicity of Cardi B, with some people affirming that she is half-Black and others vehemently denying it, but Cardi herself has said that she is both Black and Dominican, making her Afro-Latina. Kehlani is indigenous, white, and Black, making her a mixed-race woman. Nicki Minaj and Beyonce are both Black women. Thus, for the purposes of this piece, I will only be speaking on behalf of full Blackness, not being biracial, multiracial, or Latinx.

Despite claims of oppression and the inability to artistically express herself without critical repercussions, Lana Del Rey fixed her typewriter fingers to weaponize her femininity against Black women, remove Black women’s right to assert their sexual agency, typecast Black women into roles of masculinity and hardness, and deny all accountability for her actions through the vehement rejection of her microaggressive behavior.

By juxtaposing crude language and imagery alongside Black women, Lana denies us the right to our own sexual agency; instead, she infers that we promote demoralizing behaviors. Lana states that these Black women sing about "being sexy, wearing no clothes, fucking, [and] cheating," while describing herself as someone who sings about "being embodied," "feeling beautiful by being in love," and "dancing for money." Black women are often typecast as brutes by White women who intend to affirm their own sexuality and femininity at the expense of our own. In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins states that “efforts to control Black women’s sexuality lie at the heart of Black women’s oppression, [with] historical jezebels and contemporary “hoochies” [representing] a deviant Black female sexuality” (81). In order for Lana’s assertion of her own sexuality to be validated, she employs Black women as a foil. The terse and profane descriptors attached to these Black women paint them as simplistic, sexually driven beings who use their bodies to navigate throughout life, casting them into Jezebellian roles. Conversely, Lana paints herself with dainty, flowery imagery that gives herself the space to be a liberated, sexual being. She uses the presence of perceived immorality in Black women to uplift herself.

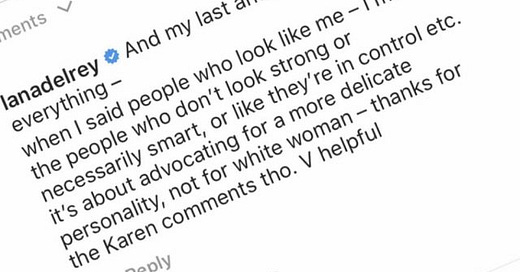

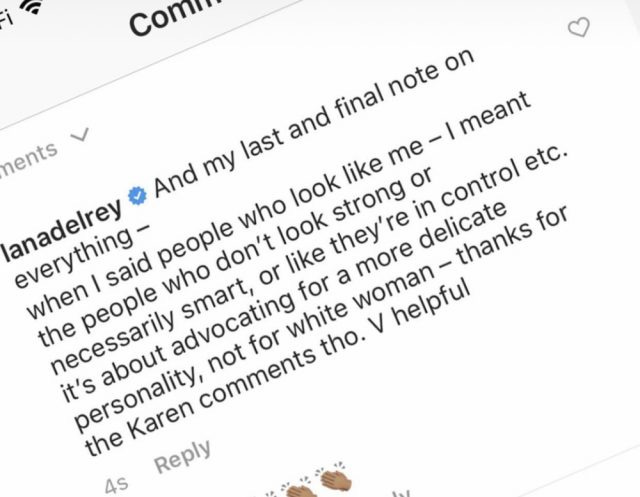

Furthermore, in her follow-up posts which only serve to further insult and dehumanize Black women, Lana doubles down on rhetoric that denies Black women the right to be soft and gentle beings. On the day of the initial controversy, she used her Instagram comment section to assert how "people … like [her]" that "don't look strong," "smart," or "in control" should be able to "[advocate] for a more delicate personality." This supports Collins’ observation that "[aggressive], assertive women are penalized … and are stigmatized as being unfeminine” (77). Lana upholds such stereotypes that label Black women as “strong” beings who never have moments of vulnerability, gentleness, or kindness. Thus, not only has she pigeonholed Black women as Jezebellian, but she has also pigeonholed us as Sapphires (also known as the angry black woman). From her perspective, delicacy appears as a luxury only afforded to women who resemble Lana in all their whiteness.

Given the loaded nature of her words, many of the women she listed in her first post (as well as Black women beyond the scope of said list) reacted with justifiable outrage. For instance, the R&B singer SZA reacted with disappointment and frustration, stating that “Black women (and men) work very hard to be seen as soft and non-threatening. We want to be seen as [gentle], soft, ethereal beings too.” She further states that, despite what Black women wear, what they choose to sing about, and how they act, our capability of displaying “vulnerability sensitivity fear and softness[sic]” should not be challenged.

Lana, however, decided to dismiss any valid criticism altogether for the sake of supporting her flimsy narrative that overlooks how the voices of white women have overtaken that of Black women in the feminist movement. In an IGTV video that she posted in the aftermath, she states that detractors have turned her words "into a race war" and claims she is "definitely not racist, so don't get it twisted." She keeps “reminding” us that she only wants to emphasize “the need for fragility in the feminist movement.“ However, she’s ignoring how Black women face the harshest scrutiny and suffering from a world that never intends to acknowledge our ability to possess gentle and kind attributes.

By denying the counterarguments which demolish her claims, she only reinforces that we are angry, promiscuous women. She affords us nothing more than that so she can frame herself as a media martyr. She infers that she has been rendered voiceless by the presence of “stronger women” who have usurped her spotlight. In an article featured in Essence entitled "Karen, Please!", Clarkisha Kent mentions that "[some] white feminists don't like to be left out of things … [especially] oppression." Lana could have based her argument upon the criticisms launched at her during the Born to Die and Ultraviolence eras of her career, but she felt the urge to compare her output to that of Black women so that she can ultimately be placed on a pedestal. In fact, Collins states that "[despite] claims of shared sisterhood, heterosexual women remain competitors in a competition that many White women do not even know they have entered" (162). Lana wields her whiteness as a sword and her womanhood as a shield so she can emerge victorious at the expense of Black women, but she refuses to listen to arguments otherwise.

Lana refuses to open her eyes to her privilege, position, and proclivity towards undermining Black women. She sees herself as a victim despite casting herself into the role of a perpetrator. She fails to recognize that her desire for "freedom of expression without judgment of hysteria" does not absolve her of the consequences stemming from how she punched down upon Black women.

Works Cited:

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge, 2015.

Kent, Clarkisha. “Karen, Please!” Essence, Essence, 7 Apr. 2020, www.essence.com/op-ed/karen-is-not-the-n-word.

P.S. If you made it this far, you might as well subscribe. Don’t be shy. Hit that button.